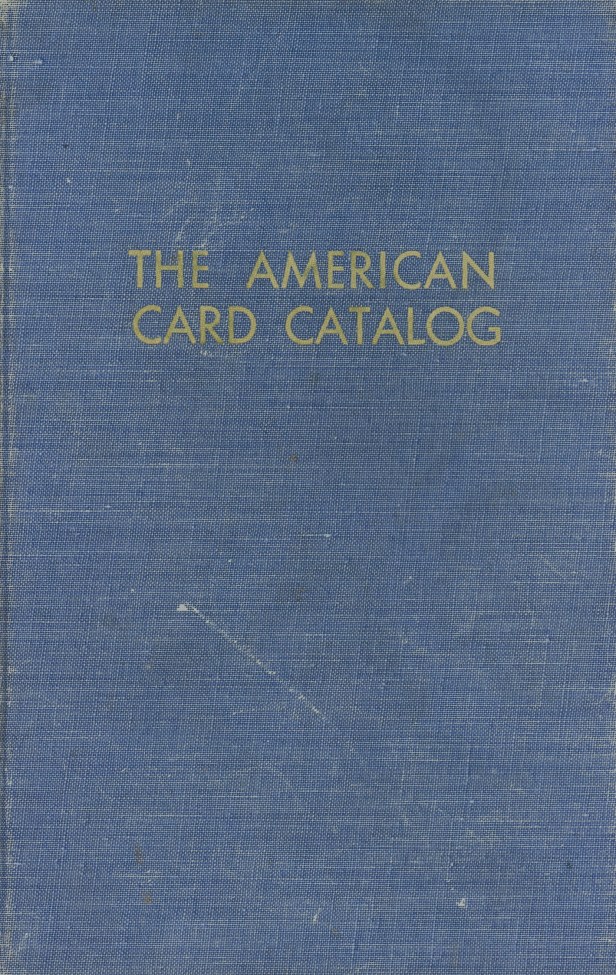

Jefferson Burdick authored the American Card Catalog, which is arguably the most important book in card collecting. Critically, the book was a massive undertaking that sought to document cards and other collectibles at a time when that information simply wasn’t available to collectors. The American Card Catalog helped to make sense of what sorts of sets were out there, how many cards appeared in them, and even provide rough values of their worth.

While few collectors actually have a copy of Burdick’s book, his fingerprints are still all over the hobby. Even today, Burdick’s cataloging system for identifying cards is still evident in the most popular of sets. While his alphanumeric codes for many sets have been replaced largely by collectors simply documenting the year and maker/issuer of a card (i.e. 1933 Goudey), many sets, such as T205 and T206, are still known almost entirely by his created designations.

Through no fault of his own, Burdick couldn’t catalog everything. And one type of card that he struggled to account for were early candy/caramel issues, known as E-Cards. Many of his listings do not even provide the number of cards in a set — likely because Burdick simply did not know. In some cases, the information he provided was even a little confusing.

Through no fault of his own, Burdick couldn’t catalog everything. And one type of card that he struggled to account for were early candy/caramel issues, known as E-Cards. Many of his listings do not even provide the number of cards in a set — likely because Burdick simply did not know. In some cases, the information he provided was even a little confusing.

That’s no surprise as some of these cards today, even with the widespread information-sharing that exists via the internet, still are not fully understood or even checklisted. But it is worth noting that even Burdick himself, the hobby’s most documented checklister, had difficulty accounting for all of the cards in many sets. That is likely the reason the book does not really provide checklists — it merely alerts collectors to which sets exist.

In particular, I’ve been looking at his cataloging of E-Cards for baseball issues. Many of them struggle to even identify how many cards are in a set. That is understandable, of course. Some, like the E104 Nadjas, have had cards discovered only in recent years, such as Fred Tenney’s card found only in 2018.

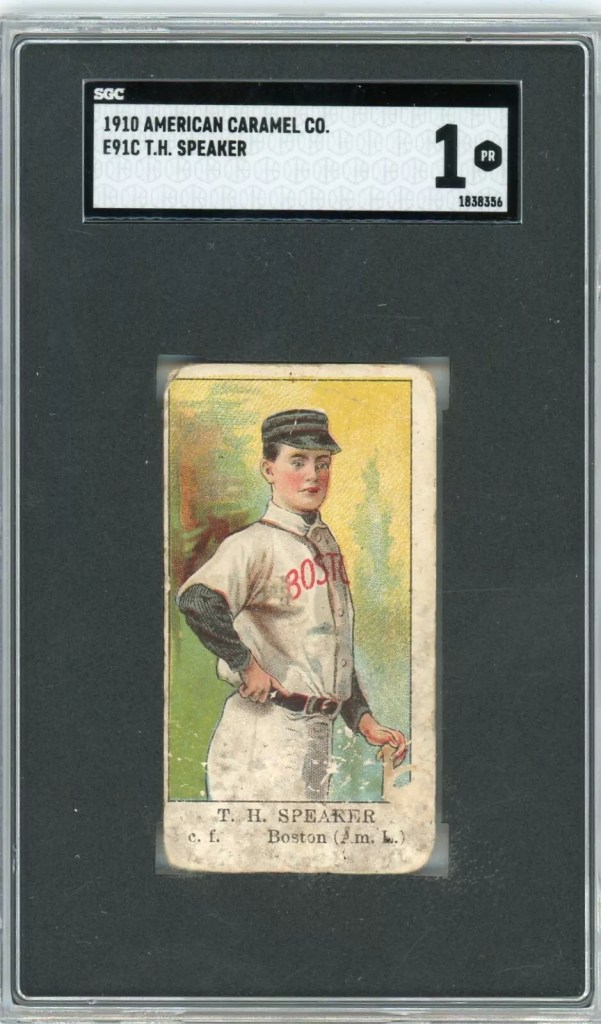

But in reviewing Burdick’s research, two relatively common sets jumped out at me. That is probably because I’ve collected both of them and have a great interest in them — the E90-1 American Caramel set and the E91 American Caramel sets.

Burdick’s E90-1 American Caramel Data

E90-1 is one of the most popular caramel card sets today. It is one of the largest and includes most of the big name players from the years in which it is believed to have been distributed (1909-11).

While we know of 121 different cards today (122 if you account for a very minor variation in Willie Keeler’s pink portrait card that includes an extra period), though, Burdick himself could only account for 111. Two things are notable about that, however.

There are a few variations of cards that Burdick may have seen but did not account for. One is Fred Clarke’s card, which is found both with an incorrect designation that he plays for Philadelphia and a later ‘correction’ with ‘Pitts’ being overprinted the incorrect ‘Phila’ team name. There is Willie Keeler’s portrait, which is found both with pink and red backgrounds. Then there is Dots Miller’s newly-identified card with a sunset in the background, which was only discovered this century.

Another theory is that perhaps Burdick only meant that there were 111 different players in the set, not accounting for pose variations. But that wouldn’t have been the case, either. Players with more than one pose would have included Kitty Bransfield, Fred Clarke, George Gibson, Roy Hartzell, Harry Howell, Addie Joss, Willie Keeler, Tommy Leach, George Stone, Honus Wagner, and Cy Young. If you count every player only once, you still wind up with only 108 cards — three fewer than Burdick’s count.

The real reason Burdick cataloged only 111 cards in the set was because that was likely all he knew of at the time. Burdick even somewhat admits to this as he states ‘111 seen’ for the E90-1 set, indicating he realized more could be out there.

How did Burdick miss at least nine cards that we know of today? The reality is that the E90-1 set has some cards that are extremely rare. None of the cards are exactly commonplace but roughly half the set can be found pretty easily. Another 30-40 cards are tougher but not too difficult. And the rest are all pretty rare or very rare. It is not within the realm of possibility that some of the really tough cards (i.e. Honus Wagner throwing, Mike Mitchell, Cy Young Cleveland, Tris Speaker, Hugh Duffy, Bill Sweeney, Jake Stahl, etc.) escaped him.

Burdick’s E91 American Caramel Data

The 1908-10 E91 American Caramel sets were also some that may have confused him. However, that isn’t as clear as it seems.

Those three sets (believed to have been issued in 1908, 1909, and 1910) are a little confusing to the novice collector, because the 1908 set (known as E91A) and the 1909 set (E91B) are pretty similar, both featuring only players from Chicago, New York, and Philadelphia. Many of the same players were used and further complicating matters, the same poses were used for different players across the three sets.

All of that said, determining the checklists for the cards was quite easy because they were printed on the backs. 33 cards appear in each set for a grand total of 99 cards. However, while Burdick did sort out that there were 33 different poses, he stated only ’82 known’ for the entire series instead of 99. What Burdick did have right was the number of total players in the three sets — 78.

All of that said, determining the checklists for the cards was quite easy because they were printed on the backs. 33 cards appear in each set for a grand total of 99 cards. However, while Burdick did sort out that there were 33 different poses, he stated only ’82 known’ for the entire series instead of 99. What Burdick did have right was the number of total players in the three sets — 78.

But where did the ’82’ come from?

At first, I thought that Burdick simply may not have counted the cards with the same player and the same pose. Several of those exist in the E91A and E91B sets and perhaps he considered them as duplicates. But that is not likely. 20 of the 21 repeated players also featured the same pose. That would have only left Burdick with 79 cards, not 82.

The more likely scenario, though, is that Burdick simply accounted only for the cards he could personally find. And, as is the case with the E90-1 set, some E91s are just very hard to find. None of the three sets are all that common and some can be extremely difficult to locate.

I do not believe that Burdick had a full checklist at his disposal and could not understand how many cards were in the set. I think that he simply accounted for them in a different manner. And as we’ve seen in both sets, while Burdick managed to find a lot of different cards, he couldn’t find them all.

Want more talk about pre-war cards? Follow me on Twitter / X here.